The legacy of Muslim art, Andalusian tilework designs transmit the historical evolution of different artistic genres. These vitrified ceramic tiles used to adorn walls and floors that constitute one of the main signs of identity in Andalusian art and architecture.

Origins and evolution

Standing out amongst the numerous artistic traditions that have taken root in Andalusia throughout history are its stunning azulejos. Distinguished for combining aesthetics and functionality, this type of decoration has its most distant origins in Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, civilizations to which the first known glazed bricks are attributed.

The application of glazed ceramic work received its definitive impulse with the blossoming of Islamic culture. The Muslims promoted the developement of new techniques that were able to exploit the full artistic potential of vitrified ceramic work, though the use of tilework really blossomed during the Nasrid period, between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. It was then that the foundations were laid for an artistic technique that would develop, incorporating various stylistic influences and technological advances.

Types of Andalusian tilework

The evolution of Andalusian tilework was marked by the changes in pictorial techniques and the manufacturing process, giving rise to clearly different styles and characteristics of each period.

NASRID TILEWORK (13th-15th century)

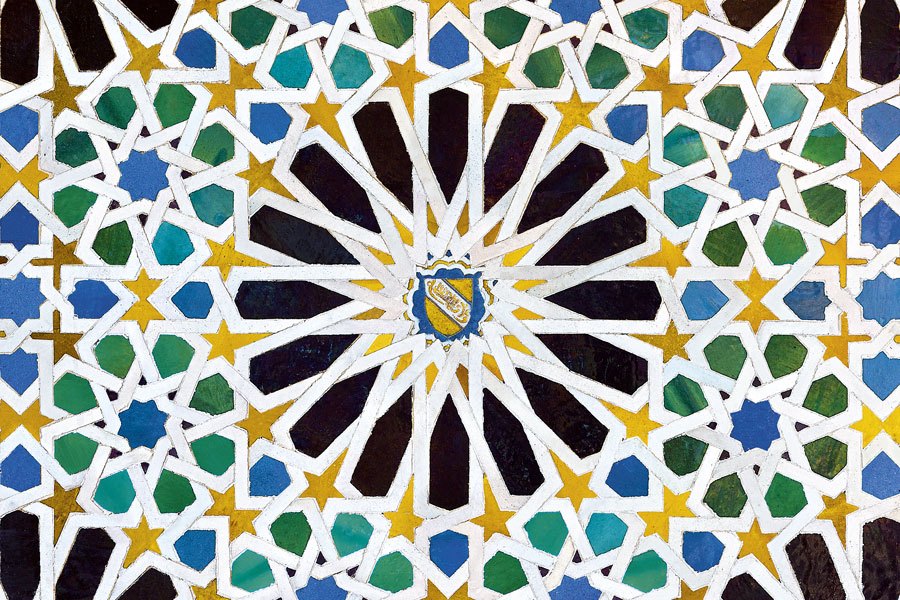

Founded in 1232 by Muhammad I in Granada, the Nasrid kingdom was the last Muslim realm in the Iberian Peninsul. The sultans of this dynasty took Andalusian art to new levels of unprecedented refinement, promoting the construction of imposing palaces where the austerity of their exteriors contrasted with the rich decoration within.

The Alhambra of Granada, the headquarters of the Nasrid court, was undoubtedly the great showcase of this period, with its striking geometric-patterned, tiled skirting boards. The Nasrid Palaces area, comprised of the Mexuar, Comares and the Palace of the Lions, has a high concentration of tilework on its walls.

The designs that are constantly repeated converted into the most recognisable element of Nasrid decorative art, although the craftsmen of this period also carried out tilework using the cuerda seca technique, in relief form and with metallic reflections. This last variety was also one of Malaga‘s specialities, the kingdom’s main production centre of ceramic work, whose golden earthenware became well known in both the Arab and Christian world.

MUDEJAR TILEWORK (14th-15th century)

From the eleventh century, the consolidation of the Christian kingdoms in the north of the Iberian Peninsula favoured a progressive expansion towards the south, into the territories of al-Ándalus. This social reality promoted the spread of artistic and technical models of Islamic origin and their fusion with Christian plastic traditions. This is how Mudejar art came into being, a hybrid style which had a particularly strong presence in the fields of architecture and crafts, such as stuccowork, carpentry and ceramics.

Tiling was a common resource in Mudejar decoration, especially in the regions where Muslim presence had been more pronounced, as in the case of Andalusia. This is proved by Seville and Córdoba, where between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries some of the most important Mudejar tilework arrangements were carried out, distinguished for preserving the essential stylistic features of their Arabic precedents.

The Royal Alcazar of Seville, designed in Mudejar style, boasts rich ornamental decoration carried out by Muslim craftsmen, in which stand out the numerous tiled skirting boards that line the walls, whose geometric designs recall the mosaics that were produced for the palaces inside the Alhambra.

ISABELLINE AND RENAISSANCE TILEWORK (15th-16th century)

The conquest of the kingdom of Granada by the Catholic Monarchs in 1492 marked the end of the last bastion of Muslim power in the Iberian Peninsula and, with it, the implementation of a new aesthetic identified with Christian precepts. At that time, the art of the kingdom of Castile was characterised by its fusion of Gothic, Mudejar and Renaissance elements.

This formal amalgam affected the decoration of Andalusian tilework, with the proliferation of tracery work, plant motifs and textile-inspired compositions. In the ceramic workshops of the city, tilework was manufactured using the cuerda seca technique, with the design painted and then coloured in, though its great demand led to the subsequent adoption of the arista method, which considerably facilitated the production process thanks to the use of moulds.

The Charles V Pavilion in Seville’s Royal Alcazar, the Casa de Pilatos or the Church of the Convent of Santa Paula are some of the places where Isabelline and Renaissance tilework can be found.

PAINTED TILEWORK (16th-17th century)

Now the centre of the world, Seville welcomed between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries numerous tradesmen and craftsmen from abroad that wanted to form part of the city’s economic boom. One of these newcomers was Francisco Niculoso Pisano, who took Andalusian tilewrok by storm. In 1490, this Italian potter established his studio in Triana, a neighbourhood with a long ceramic tradition, and he was responsible for the introduction of painted tilework, unheard of in Spain at the time.

This technical innovation was accompanied by a new creative spirit, where the artist’s freedom and inspiration were part of the pictorial design, just like the diffusion of decorative patterns typical of the Italian Renaissance. After the death of Pisano in 1529, the painted tile technique was recuperated in the second half of the 16th century, which meant that Seville’s ceramic workshops started supplying tiles to the rest of Europe and Spain’s overseas territories.

Santa Ana Church, the Palace of the Countess of Lebrija and the Museum of Fine Arts in Seville are some of the places where we can find painted tilework of the period.

BAROQUE TILEWORK (17th-18th century)

The expulsion of the Moors from the territories of the Spanish Crown, decreed by Philip III in 1609, was a serious setback for the Andalusian ceramic workshops, since a large part of their workforce belonged to this sector of the population. At this time, the Church converted into the tile industry’s best customer. This circumstance favoured the proliferation of ceramic altarpieces, which were deeply influenced by the school of Sevillian painting.

From the 18th century onwards, coinciding with the arrival of the French Bourbon dynasty to the Spanish throne, pieces of secular theme began to gain prominence, such as gallant and hunting scenes. In all cases, the pictorial motif acquired naturalism in drawing, due to the generalization of the painted tile technique.

Buildings such as the Convento de la Encarnación de Osuna and the Episcopal Palace of Malaga incorporate Baroque tilework as part of their decoration.

HISTORICIST TILEWORK (19th-20th century)

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the Sevillian ceramic workshops went into crisis due to the serious economic consequences of the war with France and the loss of the Spanish colonies in America. The sector started to grow again after the opening in 1841 of the earthenware factory of British entrepreneur Charles Pickman, located in the former Monastery of la Cartuja.

Experts on Andalusian ceramic work dedicated themselves to disseminating the styles and techniques that had fallen into disuse, leading to a period of creative splendour marked by artistic excellence and respect for the legacy of previous centuries. The tilework in the Convent de los Capuchinos in Seville, the Crópani Palace in Malaga and

Sevillian Palaces such as the Casa de los Menasque and the Palace of Monsalves boast Historicist tilework of great artistic value.

MODERNIST AND COSTUMBRIST TILEWORK (20th-21th century)

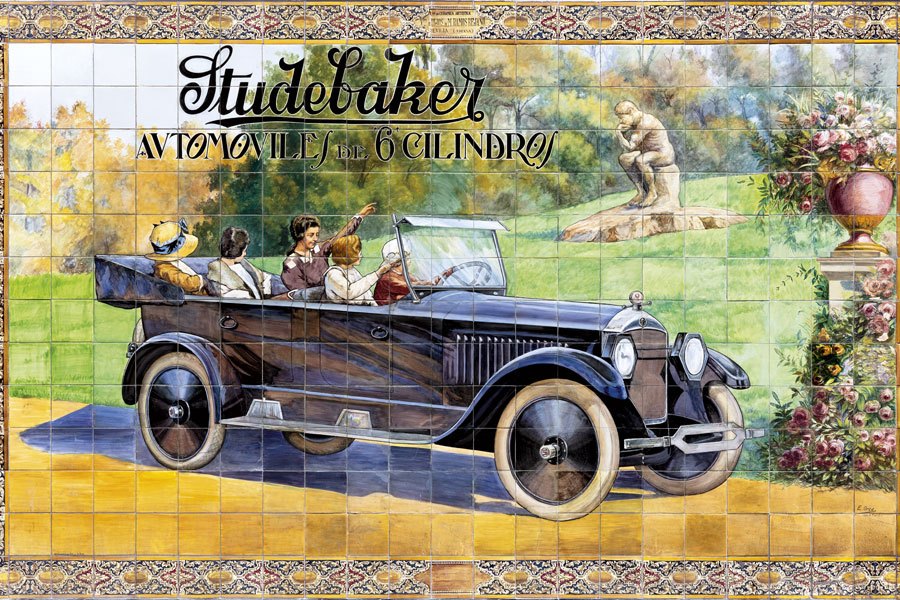

In 1929, Seville held the Ibero-American Exposition, an event dedicated to celebrating the twinning of the Iberian Peninsula and America that led to a profound transformation of the urban fabric of the city.

This circumstance led to a rising demand for tilework with typical Andalusian patterns and its popularity meant the city’s ceramic production reached an all time historic peak. At the same time, Sevillian factories benefited from the contributions of movements like Modernism, an artistic movement on ceramic painting that had its shape in very expressive compositions, dominated by the curvilinear forms of naturalistic inspiration.

At the start of the twentieth century, with the industrialisation process in the West, the use of publicity gathered force, a discipline that in Andalusia was to adopt tilework as the principle means of promotion. Thus, from the 1920s, tilework became a common element on bar signs, shop signs and all kinds of public establishments.

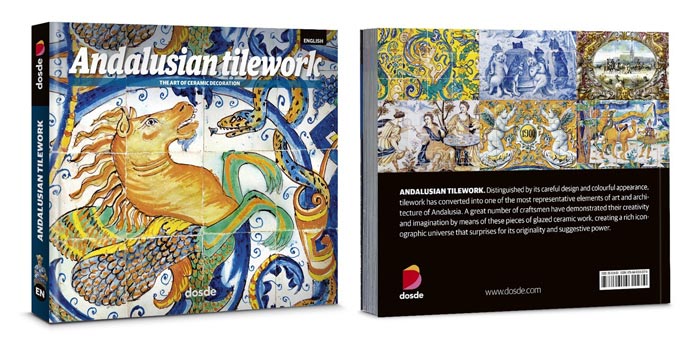

The book on Andalusian Tilework

This book on Andalusian Tilework compiles Andalusia’s most important ceramic work. By means of more than 300 photographs, their pages carry out a chronological tour of Andalusian tilework, exploring the pictorial motifs of each period.

This photographic book, published by Dosde in a compact format, shows the perfection achieved by this highly skilled technique. The book completes the thematic series of books on Seville produced by the publishing house.